Flushed with success…

Steve Bloomfield

It’s been interesting over the years to observe how shoot managers and keepers have changed the strain of pheasant stock on their shoot, seeking to achieve better sport by releasing birds with improved flying capability.

In the mid-70s when I first started in my gamekeeping career, hens were caught up towards the end of the shooting season and cock birds would be sourced from an estate several miles away in a bid to “keep the blood-line fresh” and, as far as I can remember – we never had any problems with poor flying pheasants!

I have lost count of the different strains of pheasant used on various shoots, from Michigan blue backs, Pure Kansas, Japanese Green, Bazanty, Chinese, Polish, American, Old English, Common ring necks – in fact ring-necks of all varieties. The list increases as we start to cross these breeds in a bid to achieve a smaller, faster and higher-flying bird.

But is this the answer? I have worked on shoots which were totally flat but produced excellent quality birds over the Guns when the drives were conducted with imagination. The pheasants were a more hefty variety which we referred to as the “Old English Black Neck” but they flew fast and strong.

I maintain that the size of the bird is irrelevant as long as it is fit and healthy. It is also worth remembering that the smaller you breed your bird, the smaller the price you are likely to get from the game dealer, so surely the answer should be a good-sized bird that can fly well.

Hide and seek

If it feels threatened a pheasant prefers to run and hide where possible and only really uses its wings when going up to roost or getting out of serious danger. It can take off from a standing position and power its way upwards producing an impressive burst of flight if given the opportunity. However, once this short burst is expended the bird will start looking for a landing site as soon as possible – and here lies the problem!

You will often have heard keepers congratulated for how well they presented their birds – well let me tell you, this presentation does not happen by chance, it is an art that must be learnt. There is nothing more frustrating when running a shoot than to have had a successful summer, plenty of birds on the feed rides and high expectations for the season only to experience the same old issues of birds dipping, all going over one end of the line, low flying, going back over the beaters heads, flushing all at once – you get my drift. Funnily enough, you tend not to get this on established, keepered estates. Why is this? Well, the keeper will certainly know how vital the flushing point is to the success of the day.

The vast majority of a good pheasant drive will consist of cover that is thick enough for the birds to feel hidden and safe, but thin enough to move them easily by “tapping”. This will allow them to run on ahead towards where they are to be flushed. If they are hard to move and dogs have to be used then you will be flushing birds throughout and the chances are you will not see them again over the Guns, or if you do, they will have used much of their energy already.

The positioning of the flushing point will depend on each individual drive. Are they being flushed at the end of a wood over open ground or over a ride within the wood? Either way, finding the optimum distance between flushing and maximum flying potential of the bird is crucial. As the birds move forward away from the beaters there will come a point where you will need to stop them from running too far ahead.

This can be done in a number of ways. Firstly, you could use carefully positioned “stops”. This was my least favoured option as it took valuable people out of the beating line and if not supervised they could sometimes get too excited (especially if they have a flag in their hand) and turn birds back over the beaters’ heads.

Some keepers use a flushing wire (low wire netting fence) that birds would gather against before flushing, or ‘sewelling’ (a long string with strips of plastic tied to it, which was my favoured option); these hold the birds where you want them and allow them to settle into the flushing point in a bid to evade detection – you now have the makings of a drive!

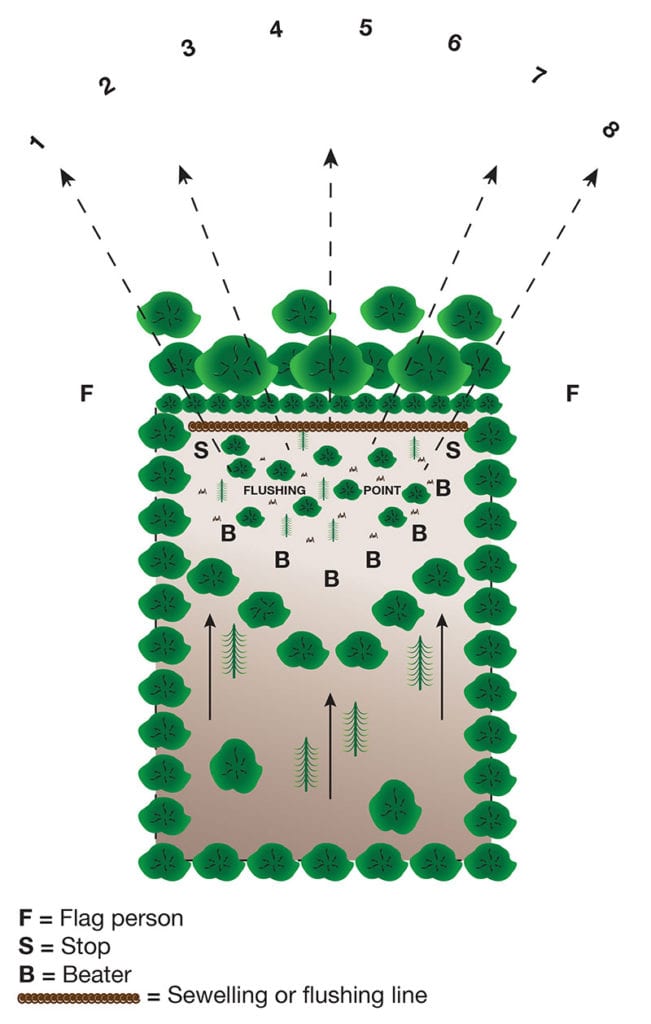

Positioning and management of the beating line along with one or two carefully positioned stops will now need to be under the strict control of the keeper. I call this a ‘closed horseshoe’ (see diagram) and it should mean no birds are able to avoid flying over the Guns.

Quiet should now descend on the drive. In fact there should be little need for noise from the beaters throughout, apart from the tapping of sticks. How the keeper manages the flush from now on will be a personal choice but whatever the system, a steady flow of birds in small flushes over the whole line of Guns is what we are looking for.

The flushing point should be a mosaic of low bushy cover in small blocks interspersed with open areas to allow birds to run forward and take off. If you have a lot of briar, make sure you break it up into small blocks. The birds will be looking for an escape route and when flushing will make for any open area of daylight to take flight. This is where you will have opened up gaps in the tree line for birds to fly through and on towards the Guns. Remember, if they have had to fight their way out of thick cover and then battle through overhanging branches, their energy will have been spent and the flight over the Guns will be weak, dipping early or flying low.

My favoured option here to control the drive was to hold the beaters in the horseshoe formation and ask them to “stand quiet”. I would then move forward on my own with the help of a steady dog and flush a few birds. Standing still and silent with the dog sitting I would watch and listen to gauge where the birds were heading and where the majority of the shooting was. When the flush subsided I would get the beaters to “rattle-up” (tap their sticks again while not moving) to move a few more birds and when that went quiet would work the dog towards the other end of the line and keep repeating the process back and forth.

This way I was controlling the flush of birds and ensuring that all the Guns were in the shooting but with plenty of time between flushes to load and get ready again. This would often go on for about 30-40 minutes and allow the building of an acceptable bag. It’s no good having a lot of birds in the drive if they all flush at once – the Guns have only got two barrels each!

At the end of the season take time to walk your woods, look at the cover and consider how and where your birds flush. Carry out maintenance each year (remember to get consent if you lease the shoot) and take into account that the dynamics of a wood will change as time goes by – a drive that was good ten years ago may not be today unless you’ve put in the work. If in doubt, seek help – the solution might just be a phone call away…

We’re here to help!

The BASC game and gundog department offer a shoot advisory service in which an experienced member of the team will visit your shoot and give expert guidance and advice on the ground. This service is open to any shoot or syndicate, no matter the size of the shoot or the number of birds released

The team will examine all aspects of your shoot from:

- Rearing and releasing birds – release pen design, construction and location

- Increase shoot returns

- Feeding and how to hold birds on your shoot

- Cover crops and creating new drives

- Habitat management

- Driving covers and improving the quality of the birds from different drives

- Providing variety on the shoot day from different game species

- Pest and predator control

- Setting up a shoot on virgin land and shoot viability

- Assessing your shoot’s potential

Our experts will be with you for the whole day so you can show them every part of the shoot that could be developed and pick their brains. You will receive a detailed written report on the areas discussed and recommendations for action.

The cost of an advisory visit for BASC members is £450 + VAT including the report (additional charges may apply if an overnight stay is required). This advisory service is also available for non-members at a price of £600 + VAT.

Please contact the BASC game and gundog team on 01244 573 019 for details or to book a visit.

For information on how you can support The Gamekeepers Welfare Trust with their 2020 campaign, click here.