All about ticks

Louise Farmer

Louise Farmer is BASC's regional officer in the Central region. She holds a degree in Veterinary Health and Applied Animal Studies and worked for over 10yrs lecturing on animal welfare, gamekeeping and deer management before joining BASC in 2016. Louise has a keen interest in wildlife management practices at home and abroad and has spent time hunting in a variety of different countries.

The tick is an arachnid parasite commonly found across the world with over 700 different species, 20 of which can be found in the UK. BASC’s Louise Farmer gives a run down of everything you need to know about these increasingly common and nasty pests.

Lifecycle of a tick

The most common species of tick present in the UK is the sheep tick (Ixodes ricinus). This is likely to be the species that you might find on your pet dog, shot deer or for those of us unfortunate enough to have had a bite on their leg or hand.

As the spring weather warms up the ground, ticks become more active and wake from a near dormant state.

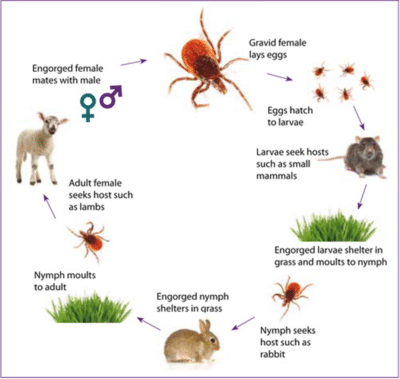

The tick follows quite a journey in its varied stages of life. Depending on when it hatches, and how successful it is finding suitable hosts, a tick can live between one-and-a-half and four-and-a-half years and will grow through three life cycle stages.

Lifecycle of a tick

Their life cycle takes several different transitions. In essence, each large feed will give them the blood meal necessary for them to grow into the next stage.

The cycle begins with an adult female laying eggs in the shelter of grass, from which larvae will hatch when the weather warms in spring.

Once hatched, the larvae will seek a small mammal or bird host and will feed for three to five days. When full, they will detach themselves from the host and drop off into the undergrowth to moult.

They morph into nymphs and seek larger hosts such as rabbits or hedgehogs. The nymph will feed for four to six days, drop off and moult into either a male or female adult tick, the largest of transitions and final life stage.

The adult tick is more likely to be easily seen by the human eye when attached and feeding from its host – a fully engorged tick can be as big as a baked bean!

An adult male will feed intermittently on a newly acquired host, while mating with females found on the same host. The adult female feeds for seven to eleven days, before detaching from the host to find a suitable habitat to lay around 2,000 eggs. This begins the next generation’s cycle.

How do ticks find their host?

The process of how ticks find their hosts is quite unique. Ticks can be found in wetter areas with longer grass, rushes, and reeds. However, pastureland and grass buffer strips are their favourite habitat as those are frequented by unsuspecting mammals.

When ready to find a host, they climb up grass stems and plants and position themselves as close to the edge as possible.

Ticks have four pairs of legs and make full use of them during this process. They hold onto the stem with the back legs and then wave their front legs out in front of them, this action is known as ‘questing’.

Their front legs are able to sense heat, moisture and movement and will reach out to grab any warm-blooded mammal that should brush past. The tick will catch on to the host and bury into the animal’s coat (or on human clothing) until it finds bare skin.

How ticks feed

This is the bit that might make you wince! The tick’s mouth consists of three main parts. The centrepiece is a long sword-like structure edged with spines called the hypostome. The hypostome also has a central groove which channels the tick’s saliva into the host during the feed and the host’s blood back into the tick.

In addition to the hypostome, the tick’s mouth also has a pair of long telescopic rods which have hooked teeth at the end. These rods are called chelicerae. When the tick has found a soft and warm area of skin, it will use its chelicerae to gently course over the skin and puncture the top layer. The chelicerae work together in unison (rather like the breaststroke) to bury the hypostome deeper into the skin.

As the chelicerae are barbed, they allow the tick to embed itself deeply into the skin. As the feeding process can take days, this creates a strong anchor for the tick so it can’t to be easily knocked off.

When the tick has embedded its mouth within the skin it will begin to feed. The tick’s saliva is complex, it contains analgesic properties that suppress the immune system of the tick’s host, often keeping them unaware of the parasite feeding by suppressing pain and itchiness, and by releasing an anti-coagulant which allows for continual feeding.

Ticks spread blood-borne diseases

Diseases from ticks

Considering how small these nasty little parasites are, they can cause significant health implications to both animals and humans.

If the host animal that the tick feeds on has a bloodborne infection, the tick will ingest the pathogens and become infected itself. As ticks require multiple hosts in order to progress through the life cycle, they will feed on a number of different individuals and so spread the disease from animal to animal and across different species.

The most significant diseases that are transmitted by ticks in the UK are:

Lyme disease (Borrelia): read our blog on living with Lyme disease here.

Louping ill (LIV) is a viral infection causing a paralytic disease in sheep. Common on hill pastures in northern England and Scotland, the virus primarily multiplies within the blood and affects the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord).

Louping ill has also been diagnosed in grouse, but rarely causes disease in humans. A vaccine is available which provides good protection to livestock.

Tick-borne Encephalitis virus (TBE) is relatively new to the UK (more common in mainland Europe) although more cases have been reported here in recent years. Ticks carrying a flavivirus infection caught from small rodents are responsible for passing the virus on to humans. Symptoms in humans resemble influenza with a high fever, sometimes followed by meningitis.

Babesiosis infects red blood cells and can cause anaemia, dark urine as well as significant headaches, fever and abdominal complaints. Most people have very mild symptoms but older people and those immunocompromised are at greater risk of severe disease.

It is thought that most people will not need treatment, so it is possible that there may have been many undiagnosed cases. Babesiosis is treated with specific antibiotics.

Read our advice on how to protect yourself and your dog from tick bites.

Want to read more blogs?

Click here to head to the Offbeat section of our website to get all opinions and advice across all the topics you need to know about.